Rebecca Mari and Matteo Ficarra.

Floods are the most costly natural disaster in Europe. In the UK, they account for around GBP1.4 billion in annual losses. Yet, evidence on the macroeconomic implications is inconclusive. GDP often shows a puzzling delayed response, and prices can be pushed in opposite directions. Using a novel county level data set for England for the years 1998–2021, we estimate the impact of flooding on output and inflation at the sector level. Sectors react heterogeneously to floods, which explains well aggregate evidence. Prices respond in sectors related to both headline and core inflation, which has crucial implications for monetary policy. We further show that investing in flood defences mitigates the economic burden of floods by strongly reducing the risk of flooding.

Chart 1: Overall number of floods (left panel) and average flood extension (right panel) by ITL3 region

Notes: The left panel shows the total number of recorded floods in each ITL3 region from 1998 to 2021. The right panel shows the average flood extent for each ITL3 region, computed as the sum of the flooded area of each flood divided by number of floods.

Sources: Data from EA Recorded Flood Extents Database and authors’ calculations.

Understanding the economic impact of floods

Studying the impact of floods at county (ITL3, Chart 1) level poses an identification challenge related to adaptation capital, as a county spending more on adaptation can reduce the frequency of flood events while increasing output through a multiplying effect. Similarly, richer regions might be able to invest more in flood defences that reduce the likelihood of floods. Hence, we adopt a local projection approach à la Jordá (2005) augmented with an instrumental variable using rainfall z-scores to isolate the economic impact of flooding. We first assess the five-year reaction of aggregate GDP and inflation to an increase in the number of floods (Chart 2). In line with the literature, GDP falls by more than 1% only two years after the shock. The impact is persistent, with GDP still 2% below its initial level after five years. Inflation increases by around 50 basis points after two years, and then drops four years after the shock. Prices are still 75 basis points higher than their initial level after five years.

Chart 2: Aggregate GDP (left panel) and inflation (right panel) response to an increase in the number of floods

Notes: Dynamic impulse response functions of GDP and inflation to a one standard deviation increase in the number of floods. All specifications include ITL3 and year fixed effects. Controls include population size and one lag of the dependent variable. Standard errors are clustered at the ITL3 level. Shaded areas denote 68% and 90% confidence bands.

What lies behind the delayed reaction of output and the erratic behaviour of prices? Our sector level analysis offers an explanation (Chart 3 and Chart 4). Output and prices respond heterogeneously not just in terms of magnitude, but also in terms of timing and sign depending on the sector. In manufacturing of textiles, manufacturing of food, beverages and tobacco, wholesale trade and retail trade the impact of floods is immediate and temporary. Within the first year following the increase in flooding, output declines by around 14% in the manufacturing sectors, 10% in wholesale trade and 4% in retail trade before reverting to its initial level. On the other hand, in the construction and food and beverage sectors output falls significantly and persistently by 10% and 6% respectively only three years after the shock. One possible interpretation of these results is that manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers, because of their reliance on large inventories and plants, incur immediate yet temporary losses. The impact might then propagate to other sectors more gradually. These sectors rely on stable supply chains, and disruptions from flooding can have persistent effects on their productivity. Floods cause damages to public infrastructure such as roads and bridges as well as to private properties, forcing temporary displacements. The former generates an increase in the demand for services in the civil engineering sector, while the latter pushes up demand in the accommodation services sector. In both sectors output temporarily increases by 10% the year of the shock. To sum up, at sector level output reacts heterogeneously to the occurrence of a flood: while some sectors exhibit a decline, others are not affected until one or two years later, and some experience temporary growth. In the longer run, economic activity declines in most sectors. This translates into the delayed impact we find at the aggregate level and highlights the importance of disentangling sector level dynamics.

Chart 3: Output response to an increase in the number of floods by sector

Notes: Dynamic impulse response functions of GVA to a one standard deviation increase in the number of floods. Estimates are based on LP-IV. All specifications include ITL3 and year fixed effects. Controls include population size and one lag of GVA. Standard errors are clustered at the ITL3 level. Shaded areas denote 68% and 90% confidence bands.

The impact of floods on prices is hard to determine a priori. Floods cause loss of capital and inventory, suspension of business activities and repair costs, all of which can pressure firms to increase prices and result in a supply side shock. At the same time, they damage properties and workers, reducing households’ ability to spend as in a demand side type of shock. Our results suggest that prices too react heterogeneously depending on the sector of activity. Deviations in output are not always accompanied by variations in inflation, with floods generating no pressure on prices in manufacturing of food, beverages and tobacco and in construction. Inflation temporarily declines on impact by 70 basis points in other manufacturing, repairs and installation activities, and by 40 basis points in accommodation and in food and services. The different timing of the response of output and prices in these sectors makes it hard to draw conclusions with respect to supply and demand channels. This is not always the case. In the wholesale and retail trade sector, floods are akin to a demand shock. Prices drop alongside output by around 25 basis points after two years and are still 75 basis points lower than their initial level five years after the shock. In manufacturing of textiles, on the other hand, the increase in output is preceded by a 300 basis points increase in inflation, suggesting a supply side mechanism at play coherent for instance with a destruction of inventories. These findings reconcile the opposite views in the literature over the nature of floods by showing that they can be both a supply and demand type of shock, depending on the sector. Whether one outweighs the other at the aggregate level likely depends on the sectoral composition of the economy. Moreover, our results challenge the commonly held idea that climate change only affects headline inflation through food and energy prices by producing evidence that floods can cause fluctuations in core inflation related sectors too.

Chart 4: Inflation response to an increase in the number of floods by sector

Notes: Dynamic impulse response functions of inflation to a one standard deviation increase in the number of floods. Estimates are based on LP-IV. All specifications include ITL3 and year fixed effects. Controls include population size and one lag of inflation. Standard errors are clustered at the ITL3 level. Shaded areas denote 68% and 90% confidence bands. For representativeness reasons we aggregate inflation measures for wholesale trade and retail trade (wholesale and retail trade), accommodation services and food services (accommodation and food services) and civil engineering and construction of buildings (construction).

We investigate two potential mechanisms behind our baseline results, namely investments and real-estate transactions. We find that investments cannot explain the persistent decline in aggregate GDP and are only partially responsible for the decrease in manufacturing output. On the other hand, in the real estate market both the number and value of real estate transactions drop. Households thus see their wealth decrease and cut their spending, in line with a demand-side type of response.

The role of adaptation spending

Adaptation does not tackle the issue of flooding at its core, namely climate change, but represents the most readily available tool to contain the impact of flooding. Nevertheless, there is to date limited evidence assessing the effectiveness of adaptation policies, which in this context refers to the extent to which flood defences can reduce the frequency of floods and the severity of the economic damages they cause. We answer this question using local authorities’ balance sheet data on flood defences expenditure.

We find that adaptation strongly reduces the likelihood of being hit by a flood in flood-prone regions, that is regions hit by more floods than the country average, especially if adaptation capital is built over time (Chart 5). A one percentage point increase in adaptation expenditure as a percentage of GDP pushes down the number of floods hitting local authorities two to four years later, regardless of flood proneness. When focusing on adaptation capital, we find that an increase in its stock as a percentage of GDP strongly and consistently reduces flood events in flood prone areas over time. A flood prone ITL3 region expanding its stock of flood defences capital by the median amount in the sample (0.002% of GDP) is hit by 0.4 fewer floods after five years. Considering that the average local authority is flooded 2.3 times yearly, a doubling of the investment in flood defence capital to only 0.004% of GDP would translate into a nearly 10% reduction.

Chart 5: Adaptation policy – extensive margin

Notes: The dependent variable is the number of floods in local authority i at time t+h. Each dot represents the reduction in the number of floods following either a one percentage point increase in adaptation expenditure as a percentage of GDP in regions that are prone (green line, left axis) and not (dark blue line, right axis) to flooding, or a one percentage point increase in the stock of adaptation capital as a percentage of GDP in regions that are prone (light blue, left axis) and not (orange line, right axis) to flooding. A region is prone to flooding if in an average year it is hit by more floods than the country average over the panel (2.3 floods). Adaptation capital is computed by cumulating adaptation expenditure over time and assuming a depreciation rate of 50 years. Regressions include three lags of the dependent variable, population size and one lag of GDP. All regressions include ITL3 and year fixed effects, and standard errors are clustered at the ITL3 level. Hollow dots correspond to non-significant coefficients, full dots correspond to coefficients statistically different from 0.

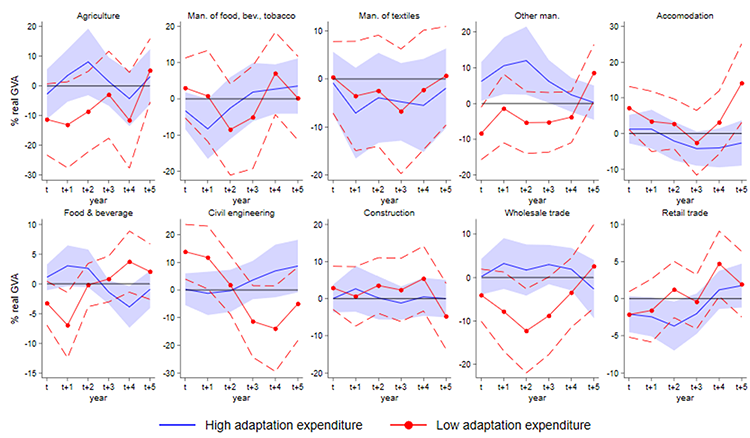

Next, we analyse whether investing in adaptation can reduce economic losses once a flood happens (Chart 6). With the exception of construction and manufacturing of textiles, the difference in the impact of floods on output between high and low adaptation expenditure regions is sizeable. However, the overlap in the confidence intervals suggests that this difference is hardly significant. Still, the positive output growth detected in civil engineering and accommodation services following a flood seems to be driven by local authorities that spend less on flood defences. Similarly, the decline in output for wholesale trade and food and beverage services comes mostly from low expenditure areas. For these four sectors, investing more in adaptation likely reduces the destructive power of floods by limiting the overflow of water or delaying it.

Chart 6: State dependent output response to an increase in number of flood by sector

Note: Dynamic impulse response functions of GVA to a one standard deviation increase in the number of floods: high (blue line) and low (red line) adaptation expenditure state. The state is defined using a regime-switch dummy as in Ramey and Zubairy (2018) that takes value one if ITL3 area I spent more than the panel average on adaptation in year t-1. Estimates are based on LP-IV. All specifications include ITL3 and year fixed effects. Controls include population size and one lag of GVA. Standard errors are clustered at the ITL3 level. Shaded areas denote 90% confidence bands.

Conclusions

The economic impact of floods is significant and highly uneven across sectors. We find sector level heterogeneities that explain well the aggregate results in the literature, offering a possible explanation for the delayed response of GDP and the demand versus supply debate. For policymakers, this evidence means that a one size fit all approach is not the most effective response. While our results are not conclusive as to the dynamics of aggregate inflation, they uncover significant price variations in sectors related to core inflation, and not just headline. This finding, combined with the expected increase in flooding because of climate change, should be kept in mind by central banks. Our results also stress the importance of building up adaptation capital to reduce the risk of flooding.

Rebecca Mari works in the Bank’s Monetary Analysis, Structural Economic Division and Matteo Ficarra is a PhD researcher at Geneva Graduate Institute.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “Weathering the storm: the economic impact of floods and the role of adaptation”

Publisher: Source link