Isabelle Roland, Yukiko Saito and Philip Schnattinger

The Bank of England Agenda for Research (BEAR) sets the key areas for new research at the Bank over the coming years. This post is an example of issues considered under the Prudential Architecture Theme which focuses on the evolving regulatory structures and fresh strategic issues for regulators and supervisors.

Interventions in corporate credit markets have featured prominently in the policy response to crisis episodes over the last two decades. Loan forbearance features prominently among those interventions by lenders and/or regulators. It is a practice whereby banks grant temporary relief to struggling borrowers, to avoid default. On balance, the literature is critical of loan forbearance in the corporate sector because of its potential to contribute to zombification – a situation where bank lending keeps unproductive firms alive, resulting in lower aggregate total factor productivity. Results from our new paper show that forbearance lending in combination with business restructuring plans can provide temporary relief for struggling firms, safeguarding output and employment, without contributing to the zombification of the corporate sector. Note that our research is focused on the impact of forbearance on the corporate sector; the impact of forbearance on lenders is a separate question outside the scope of our paper.

The small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) Financing Facilitation Act as a quasi-experimental setting

In our research, we focus on evaluating a unique large-scale corporate forbearance scheme, namely the Japanese SME Financing Facilitation Act of 2009. This intervention provides us with a quasi-experimental setting because it mandated all banks to offer loan forbearance to SMEs that asked for support and met a range of eligibility criteria outside of the banks’ control. At the same time, the regulator amended supervisory guidelines to allow financial institutions to exclude these restructured SME loans from their reported non-performing loans under the condition that they produced business restructuring plans that were expected to make the loans perform again within five years. Although there was no formal penalty imposed on banks for rejecting applications, almost all requests were accepted, reflecting informal pressure from the government for banks to accept all applications.

Framework for policy evaluation

We analyse the policy in four steps. First, we develop a search and matching model of the credit market where banks have incentives to forbear. Second, we use firm-level data from Tokyo Shoko Research (TSR) to estimate the impact of the policy on the average loan interest rates paid by firms using a difference-in-differences (DiD) specification guided by the model. To do so, we build a measure of firm-level exposure to the policy using survey data from the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI). Third, we use the model and the estimated annual treatment effects on interest rates to conduct back-of-the-envelope counterfactual exercises. We ask ourselves what would happen to the aggregate capital stock, output, and capital productivity if the policy had not been enacted. In other words, we remove the annual interest rate subsidy generated by the policy, let firms adjust their capital and labour input in response to the resulting change in the cost of capital, and calculate the aggregate capital stock, capital productivity, and output produced in this counterfactual economy. We then compare them to their observed equivalents. Finally, we examine whether the Act contributed to the creation of zombie firms using a DiD framework.

Forbearance generated substantial credit subsidies

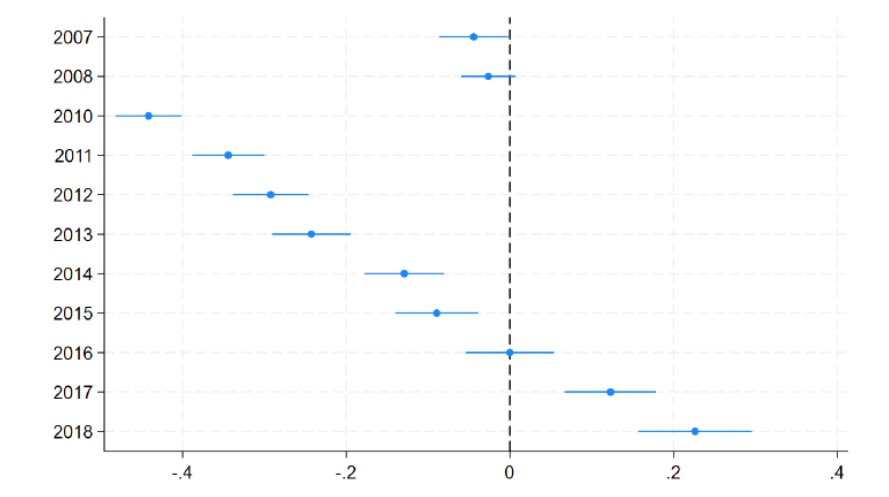

Chart 1: Event-study plot – treatment effects on average interest rates

Notes: Chart 1 presents the annual treatment effects on average loan interest rates from the DiD estimation, ie the coefficients on the interaction between annual dummy variables and treatment exposure, and their 95% confidence intervals. For example, a coefficient of about -0.4 in 2010 corresponds to the law depressing average interest rates by 40% in that year.

We plot the estimated effects of the policy on average loan interest rates in Chart 1. While there is no significant effect before the law was passed in 2007–08, we find that the Act worked as an interest rate subsidy from 2010 onward. On average, it depressed interest rates by about 18.5% for treated firms over 2010–18. The effects are large in the years closer to the implementation of the Act and fade away over time. The effect switches sign and becomes positive in 2017, reflecting a weakening of forbearance incentives over time. Indeed, most forbearance was granted in the form of temporary payment deferrals (as opposed to debt forgiveness). Firms that received payment deferrals experienced a period of subsidised credit before returning to higher interest rates (potentially higher than before the policy).

Credit subsidies boosted the aggregate capital stock at the expense of productivity

Table A: Aggreagte counterfactuals

| Counterfactuals – % change | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Mean |

| Capital stock | -4.22% | -3.76% | -3.46% | -3.43% | -1.58% | -1.07% | 0.20% | 2.09% | 2.97% | -1.36% |

| Capital productivity | 1.47% | 1.38% | 1.12% | 1.23% | 0.53% | 0.36% | -0.07% | -0.76% | -0.87% | 0.49% |

| Output, without reallocation | -8.30% | -6.64% | -5.86% | -5.59% | -2.44% | -1.66% | 0.30% | 2.89% | 4.42% | -2.54% |

| Output, with reallocation | 4.78% | 5.86% | 2.91% | 1.53% | -0.36% | -1.64% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.45% |

Notes: Table A presents the results from removing the annual treatment effects presented in Chart 1. The percentages show the annual deviations between counterfactual aggregate output, capital stock, and capital productivity and their observed equivalents. For example, -4.22% for the capital stock in 2010 means that the capital stock would have been 4.22% lower in 2010 if the policy had not been enacted.

The counterfactuals in Table A indicate that cheap credit boosted the aggregate capital stock at the expense of aggregate productivity. The Act boosted the aggregate capital stock by 1.4% and depressed capital productivity by 0.5% on average over 2010–18. The extent of credit reallocation determines whether the policy leads to output gains or losses. We perform the counterfactuals under two scenarios for what happens to the capital that is freed up by the removal of the annual subsidy. First, we assume that the capital freed up from treated firms is not reallocated to other firms. Second, we assume that the freed-up capital is seamlessly reallocated to firms that produce at counterfactual aggregate capital productivity (ie, the aggregate productivity of untreated firms). In the first scenario of subdued credit reallocation, the Act is estimated to have boosted output by 2.5% on average. By contrast, if we assume seamless credit reallocation, the Act is estimated to have depressed output by 1.5% on average. Since capital reallocation is pro-cyclical, ie, depressed during recessions, the first scenario is more plausible and provides an upper-bound estimate of output gains.

Forbearance did not contribute to the zombification of the corporate sector

Finally, we examine whether the Act contributed to the creation of zombie firms. More specifically, we explore the impact of the policy on exit, total factor productivity (TFP), interest coverage ratios (ICRs), defined as earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) over interest expenses, and the probability that a firm is classified as a zombie in a DiD set-up. Zombie firms are identified by a set of criteria indicating both financial distress and ongoing support from lenders, typically in the form of subsidised credit. On the one hand, we find that the policy reduced debt-servicing pressures (ie increased ICRs) and decreased the probability of bankruptcy. On the other, the policy improved firm-level TFP and, surprisingly, reduced the probability that a firm is classified as a zombie. In other words, the policy achieved its stated goal of propping up the SME sector without contributing to zombification. This indicates that implementing mandated business restructuring plans, a prerequisite for avoiding loan classification as non-performing, contributed to the recovery of distressed SMEs.

Policy insights

Our results contribute to the literature by challenging the view that loan forbearance necessarily contributes to the zombification of the corporate sector. Importantly, when combined with business restructuring plans, forbearance can provide temporary debt relief for struggling firms that are otherwise solvent and will recover from a temporary shock. In other words, a carefully designed credit market intervention based on forbearance has the potential to be used as part of the policy toolkit to respond to severe stress episodes in the corporate sector, especially those that are accompanied by credit market disruptions. To the extent that banks grant forbearance to viable firms, such an intervention can enable the latter to weather temporary difficulties while limiting the negative impact on aggregate productivity in the short and long term.

Isabelle Roland works in the Bank’s Macro-Financial Risks Division, Yukiko Saito works in the Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University, Tokyo, and Philip Schnattinger works in the Bank’s Structural Economics Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “Forbearance lending as a crisis management tool”

Publisher: Source link