Carlos Cañón Salazar, John Thanassoulis and Misa Tanaka

Several global financial centres, including London, Hong Kong and Singapore, are overseen by financial regulators with an objective on competitiveness and growth. In a recent staff working paper, we develop a theoretical model to show that some competitive deregulation can arise when several regulators are focused on growth, though not a ‘race-to-the-bottom’: regulators will not lower regulations to levels favoured by banks if the costs of financial instability are large. To maintain competitiveness and stability of the UK as a global financial centre, there is a need for a comprehensive strategy which takes into account both regulatory and non-regulatory measures. This may require coordination across multiple institutions.

How much do financial regulators care about growth?

In 2023, the UK’s Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) acquired a secondary competitiveness and growth objective to facilitate, subject to aligning with relevant international standards, the international competitiveness of the UK economy (in particular the financial services sector) and its growth over the medium and long term. The PRA is not unique in having such a growth objective. For example, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has a development objective of growing Singapore into an internationally competitive financial centre. Similarly, helping to maintain Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre is one of the key functions of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA).

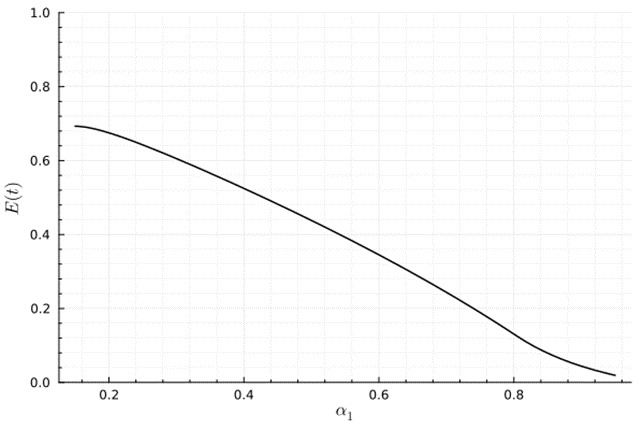

To gauge the extent of growth-focus of regulators, we conducted a textual analysis of 2013–23 annual reports by the Federal Reserve Board (FRB), the European Banking Authority (EBA), the MAS, the HKMA and the PRA to produce a crude measure of how often growth-oriented words are used relative to stability-oriented words. Based on this measure, which indexes the EBA’s level in 2013 as 1, the MAS and the HKMA appear to have been more growth focused – at least in their published documents – than the PRA, the FRB, and the EBA over the last decade (Chart 1). Our measure also detects an uptick of PRA’s growth focus in 2023 after it was given its secondary growth and competitiveness objective.

Chart 1: Growth preference – cross country comparison, 2013–23

What happens when regulators compete?

What happens when several regulators have a growth objective? To answer this question, we developed a game-theoretic model. In our model, regulators in two financial centres have an objective function which consists of a weighted sum of the output from financial intermediation (‘growth objective’) and the expected loss from bank failures (‘stability objective’). The ‘growth-focused’ regulator 2 has a higher weight on the growth objective than the ‘stability-focused’ regulator 1. Regulators set the level of ‘regulatory stringency’ (parameter t in our model) to maximise their objectives: this captures the full package of regulatory and supervisory requirements, including capital and liquidity requirements, but also the intrusiveness of supervisory oversight and the acceptability of different business models. Increasing the level of regulatory stringency lowers the probability of bank failure but also increases the operating costs for banks.

Some banks are committed to operating in a specific country because it is attractive for non-regulatory reasons. Indeed, regulatory environment is only one of the many factors which determines a city’s ranking in the Global Financial Centres Index 36: other factors such as taxation, availability of skilled workers, and infrastructure also matter. But some other banks are willing to move their operations to any country in response to the relative level of regulatory stringency. Banks can bluff and pretend to be mobile, so the regulators cannot observe which banks are truly internationally mobile and thus they respond by setting the same standard for all banks.

The level of regulatory stringency affects growth in our model by influencing the number of banks attracted to the country. In turn, these banks support increased commercial activity by matching international capital with productive investment opportunities. Internationally mobile banks move to countries which allow them to maximise their profits, and so they move to countries which offer lower levels of regulatory stringency. However, there will be a level of stringency below which profits decline: banks don’t like regulatory stringency below this level as they don’t want to operate in a poorly regulated, unstable environment.

As a benchmark we consider the following thought experiment. Suppose that regulators are operating in a closed economy in which no bank can move abroad. In this case, regulators will set the regulatory stringency to maximise the expected benefit per bank by weighing expected output against expected cost of failure. Moving to our core analysis, suppose that regulators are operating in an open economy, where some banks can move abroad. Regulators are now competing with each other, so will set the level of regulatory stringency to also take into account its impact on attracting mobile banks. If it is set too high, none of the mobile banks will come, so the expected output generated by the financial sector will be low. But if it is set too low, the regulator will attract mobile banks but only at the expense of increasing all banks’ failure rate: so the expected cost of bank failure will rise and the expected output could also be low.

We call the resulting equilibrium ‘competitive deregulation’. It is a situation where a regulator may set the level of regulatory stringency below its closed-economy optimal level to attract internationally mobile banks. An extreme version of this is a ‘race to the bottom’, which we define as a situation whereby the regulatory stringency is driven to the level preferred by banks. We show that, although competitive deregulation can arise, regulators will not race to the bottom to set the regulatory stringency to levels preferred by banks if the expected cost of bank failures is large and their mandate, usually set by the government, requires them to limit this cost.

What happens when regulators are given a stronger growth mandate?

The next step in our analysis is to ask how the levels of financial regulation will respond when a government revises its regulator’s mandate to increase its focus on growth.

We show that, if the growth-focused regulator 2 becomes even more growth focused, then competitive deregulation may be mitigated. This is because the stability-focused regulator 1 becomes less willing to compete as it expects its rival to compete more aggressively to secure all the mobile banks. Numerical simulations in Chart 2 show that the expected level of regulatory stringency offered by the two regulators (on the y-axis) stays fairly stable as regulator 2 becomes more growth focused (as alpha-2 on the x-axis increases): it initially increases modestly, then decreases. This suggests that a stronger growth mandate does not necessarily result in competitive deregulation.

Chart 2: Expected regulatory stringency is fairly stable as growth-focused regulator becomes more growth focused

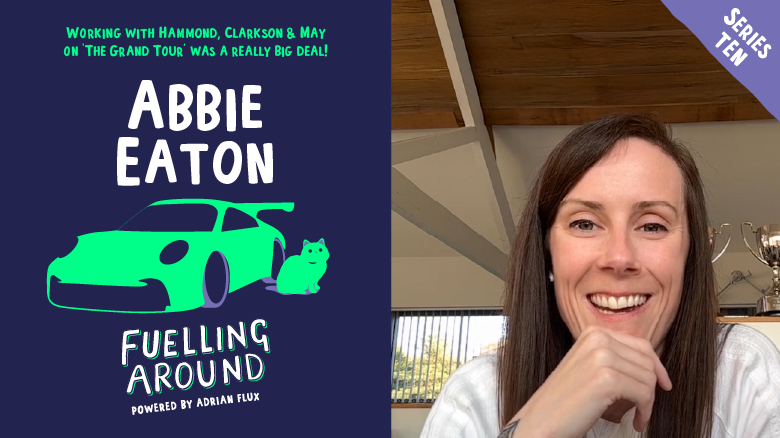

However, competitive deregulation results if the stability-focused regulator 1 becomes more growth focused. Regulator 1 competes more aggressively and lowers its average level of regulatory stringency. The growth-focused regulator 2 responds to this challenge, so it too lowers its level of regulatory stringency. It follows that competitive deregulation intensifies and the expected level of regulatory stringency declines. Numerical simulations, in Chart 3, show that as the growth focus of regulator 1 becomes more prominent (alpha 1 on the x-axis increases), and approaches that of regulator 2, the expected level of regulatory stringency declines.

Chart 3: Expected regulatory stringency falls as stability-focused regulator becomes more growth focused

The strategy of the regulators also depends on how many banks are willing to move, which depends on the relative stringency of financial regulation – and this will in turn depend on non-regulatory issues such as taxes and labour laws which also determine the attractiveness of a country. If more banks are internationally mobile, the growth-focused regulator will lower its regulatory stringency to attract them. But the reaction of the stability-focused regulator is ambiguous, as it weighs the benefit of attracting a larger pool of mobile banks against the cost of having to deregulate more to compete against the more aggressive rival.

A global financial centre needs a comprehensive strategy to flourish

Our analysis has a number of policy implications. First, setting global regulatory standards would help limit the extent of competitive deregulation. However, in practice, it is not always possible to agree on and enforce global standards across all dimensions.

Second, setting hierarchical objectives, whereby the growth objective is made strictly secondary to the stability objective (as in the case of the UK’s PRA), could be another way of limiting competitive deregulation. To ensure that the stability objective remains strictly primary, regulators could monitor a set of quantitative indicators for its primary stability objective.

Finally, there will be less need for financial regulators to use regulatory stringency to attract financial institutions if they become committed to staying in the country because it is attractive in other dimensions. This calls for a comprehensive strategy, which takes into account both regulatory and non-regulatory measures, to maintain both competitiveness and stability of the UK as a global financial centre.

Carlos Cañón Salazar and Misa Tanaka work in the Bank’s Research Hub and John Thanassoulis is a Professor at the University of Warwick.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “Global financial centre and its regulators: what’s the strategy when everyone wants to be the top dog?”

Publisher: Source link