Nicolò Bandera and Jacob Stevens

How should the central bank conduct asset purchases to restore market functioning without causing higher inflation? The Bank of England was faced with this question during the 2022 gilt crisis, when it undertook gilt purchases on financial stability grounds while inflation was above 10%. These financial stability asset purchases could have counteracted the monetary policy stance by easing financial conditions at a time when monetary policy was tightening them. Did a trade-off between price and financial stability arise? In our Staff Working Paper, we find the asset purchases stabilised gilt markets without materially affecting the monetary policy stance. This was only possible because the intervention was temporary; highly persistent asset purchases would have created tension between price and financial stability.

We develop a detailed Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium model featuring liability-driven investment funds (LDI funds) and pension funds to replicate the gilt crisis. An explanation of what LDIs are and their role in the 2022 crisis is available in this recent Bank Underground post. Having realistically replicated the crisis dynamics, we turn to modelling financial stability interventions: first the actual Bank of England asset purchases and then two counterfactual policies, a repo tool and a macroprudential liquidity buffer. This allows us to estimate the monetary policy spillovers generated by each financial stability intervention and identify the conditions to minimise them, ensuring the central bank’s effectiveness in delivering its mandate.

Replicating the 2022 UK LDI crisis

We replicate the gilt crisis with an exogenous ‘portfolio shock’, capturing the same effects as an increase in default risk (ie, higher yields on long-dated UK government bonds). This drives down the price of both nominal and index-linked gilts and, before we introduce LDIs, the price of both falls by the same amount. Once we include LDIs into our model, the price of index-linked bonds falls even more sharply. This replicates the actual changes in gilts’ prices – see Chart 1 below – following the ‘Growth Plan’ (also referred to as ‘Mini Budget’, this plan featured a sharp rise of the UK national debt over the medium term to fund measures intended to increase economic growth).

Chart 1: UK gilt prices after the ‘Growth Plan’

Note: Chart 1 shows the change in price for all UK gilts between 20 September and 27 September 2022.

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Tradeweb and Bank calculations.

What is the mechanism in our model that exacerbates the fall in price of index-linked gilts? Fire sales by LDIs. When bond prices fall, leveraged LDIs suffer large and unanticipated losses. This leaves them with a low or even negative net-worth and sharply increases the leverage ratio. However, by contract with their customers (pension funds) LDIs must keep leverage below a certain threshold. This requires them to either raise new equity or to sell assets and pay off some of their debt.

Reflecting actual market segmentation and institutional sluggishness, two features of the model prevent the first option from happening: first, pension funds are separated from LDIs; second, pension funds decide their asset holdings – including LDI shares – a period in advance. This means that while pension funds can inject equity into the LDIs, they cannot do so quickly, reflecting the pension funds’ actual operational difficulties in changing portfolio composition at short notice. Hence in our model, and as in September 2022, LDIs are left with the second option: deleveraging through assets’ sales. This second option is extremely unpleasant for the LDIs due to their dominant market position (in the UK LDIs are by far the largest holders of very long-term gilts and index-linked gilts): if they attempt to reduce leverage by selling assets, they are selling to an illiquid market with very few buyers. This pushes down on gilt prices even further, causing even further losses for LDIs and mandating still more sales. This is exactly the fire-sale dynamic observed in 2022.

Our model suggests there are three key variables which determine the size of fire sales and hence the extent of gilt-market dysfunction: the size of the LDI sector, the leverage of the LDI sector, and financial frictions in the gilt market. This last variable is crucial. If other financial institutions are able to arbitrage the index-linked gilt market, then LDIs’ gilt sales have no effect on prices and gilt markets remain efficient. In 2022, they proved unable to do so, triggering the intervention by the Bank of England.

Modelling the Bank of England intervention

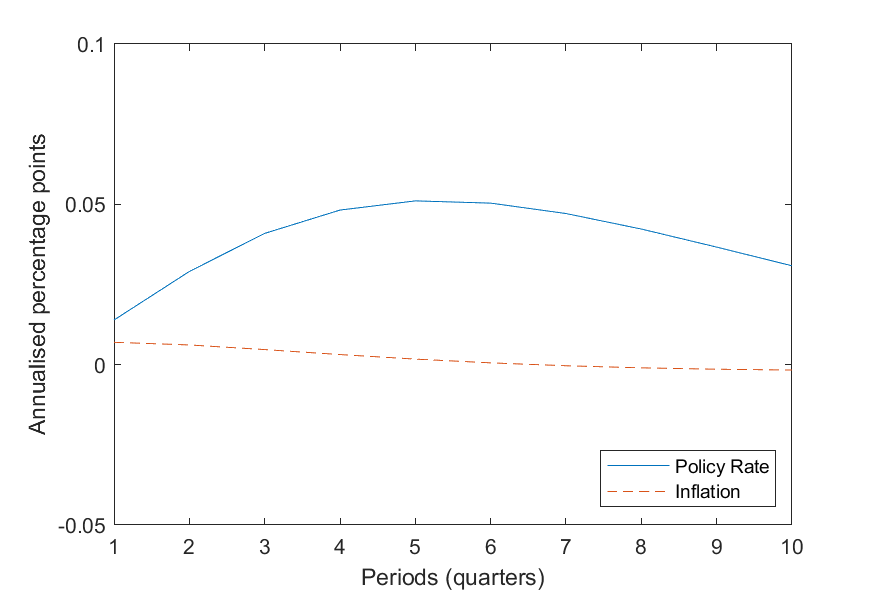

We model the Bank of England intervention as unanticipated purchases of gilts worth 0.9% of GDP (the eventual size of the programme) unwound over 3–6 months. Chart 2 shows the effect of this intervention on the price of index-linked and nominal bonds, as estimated by our model. We find that the intervention was successful at restoring gilt market functioning: the spread between linked and nominal bonds almost completely closes. In addition, Chart 3 shows the impact of these asset purchases on the Bank Rate and inflation, which we interpret as monetary policy spillovers. We find that the asset purchase intervention had minimal monetary policy consequences. This was one of the key design intentions of the policy response due to inflationary concerns at the time and our results strongly support the idea that this design was effective. A small increase in Bank Rate of 1–5 basis points is sufficient to accommodate the intervention and almost completely eliminates inflationary effects. This can be readily accommodated within the regular course of monetary policy decision-making, without necessitating an unscheduled special session.

Chart 2: Financial stability intervention: effect on bond prices

Note: Chart 2 shows the effect of a risk-premium shock on bonds prices in an economy with (red dashed line) and without (blue line) asset purchases worth 0.9% of GDP (the eventual size of the Bank programme) as estimated by our model.

Chart 3: Financial stability intervention: effects on the Bank Rate and inflation

Note: Chart 3 shows the impact of asset purchases worth 0.9% of GDP on the policy rate (blue line) and inflation (red dashed line) as estimated by our model. These are the monetary policy spillovers of the financial stability asset purchases.

The time-limited nature of the purchases is crucial in preventing monetary policy impacts: since the acquired assets are held for only a short period, there is no persistent decline in bond yields in the model and hence little change in saving and investment behaviour by households and firms. In the hypothetical case of a highly persistent intervention, we find that the monetary policy impacts escalate rapidly: a Bank Rate rise of 20–40 basis points becomes necessary to offset any inflationary effect generated by the asset purchases. In addition, we find that the monetary policy impacts depend on the actual speed the intervention is unwound, rather than public beliefs about the intervention. This is reassuring for central banks worrying about the communication challenge of differentiating between financial stability asset purchases and monetary policy ones.

Simulating alternative tools

In line with ongoing Bank policy development, we also model a ‘repo loan’ to pension funds worth 0.23% of GDP (a quarter of the size of the actual asset purchases) and unwound at the same speed of the actual intervention. Providing loans to LDIs is ineffective because the crisis is driven by the LDIs’ attempts to deleverage. In other words, a central bank’s repo loan would only replace one kind of leverage with another. Instead, we show that providing liquidity to pension funds – on condition they inject it into the LDIs as equity – could be effective at resolving the crisis. In our setup, loans to pension funds worth 0.23% of GDP have similar market impacts as the actual asset purchase programme worth 0.9% of GDP.

We also simulate a counterfactual macroprudential ‘liquidity buffer’ requiring the pension fund/LDI sector to hold liquid assets proportional to total LDI assets. This is in line with the increased liquidity promoted by The Pensions Regulator in the aftermath of the 2022 crisis. We explore buffers of several sizes that are then completely relaxed during the crisis. Releasing the buffer allows LDIs to run down their liquid assets rather than sell gilts. We estimate that requiring pension funds to hold liquid assets worth 2.75% of LDI assets would offset half of the ‘LDI effect’ on gilts’ prices. Even if this level of liquidity is not sufficient to resolve the market dysfunction, the problem would have been partly alleviated and any asset purchases or repo would have been significantly smaller. However, a larger liquidity buffer implies a reduced rate of return on pension fund portfolios in normal times.

Conclusions

Departing from previous UK asset purchases – deployed for monetary policy purposes (quantitative easing) – the 2022 intervention in response to the gilt crisis was designed to restore financial stability without increasing inflation. A key question is therefore how big the monetary policy consequences actually were. To answer this, we build a theoretical model to replicate the 2022 episode, the Bank of England policy response and two counterfactual policy responses. We find that the Bank of England asset purchases successfully addressed market stress without materially affecting the monetary policy stance. The temporary nature of the intervention avoided monetary policy spillovers and therefore tensions between price and financial stability.

Nicolò Bandera and Jacob Stevens work in the Bank’s Monetary and Financial Conditions Division. Jacob is also a PhD student at the University of St Andrews.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “Stable gilts and stable prices: assessing the Bank of England’s response to the LDI crisis”

Publisher: Source link