Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Alex Haberis, Federico Di Pace and Brendan Berthold

To achieve the Paris Agreement objectives, governments around the world are introducing a range of climate change mitigation policies. Cap-and-trade schemes, such as the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), which set limits on the emissions of greenhouse gases and allow their price to be determined by market forces, are an important part of the policy mix. In this post, we discuss the findings of our recent research into the impact of changes in carbon prices in the EU ETS on inflation and output, focusing on how the emissions intensity of output – the quantity of CO2 emissions per unit of GDP – affects the response. Understanding these economic impacts is important for the Bank’s core objectives for monetary and financial stability.

The EU Emissions Trading System

Before turning to the findings of our analysis, it is worth summarising briefly how the EU ETS works. The essence of the system is that the EU authorities issue a limit, or cap, on the quantity of greenhouse gas emissions for a set of energy-intensive industries (including aviation), which, together, make up around 40% of EU emissions. Over time, this cap is reduced. Note that although the scheme applies to greenhouse gases in general, for brevity we will use CO2 as a catch-all for these emissions. CO2 is perhaps the most significant greenhouse gas given how long it lasts in the atmosphere.

Subject to that overall cap, the authorities sell emissions permits to firms in the industries covered by the system. The prices of these permits are determined by market forces – firms that need a lot of energy would tend to make higher bids for the emissions permits, pushing up their prices.

The permits can also be traded in a secondary market. Eg if a firm has permits it no longer needs, it can sell those to another firm which does need them. If in aggregate firms need to use less energy, the price of permits would fall. To the extent that the permits give the right to emit a specified amount of CO2, we can view their prices as the carbon price.

Establishing a causal relationship between changes in carbon prices and economic variables

A challenge when trying to discern the effects of changes in carbon prices on the wider economy is that carbon prices themselves respond to wider economic developments. For example, if there is a slowdown in demand due to a loss in consumer confidence, we would expect to see output and inflation fall. But we would also expect to see carbon prices fall, as firms reduce their demand for energy and, hence, for emissions permits.

Naively seeing this correlation between output, inflation and carbon prices might lead an observer to believe that falls in carbon prices are caused by falls in output and inflation. However, such causal inference would be incorrect.

Instead, to be confident that an observed change in carbon prices has caused a particular change in output, inflation, or asset prices, we must be sure that the carbon price itself is not responding to some other force that is also driving the movements in our economic variables of interest.

The problem of establishing causation is known in the econometrics literature as ‘identification’. This amounts to identifying changes in carbon prices that are independent of any changes in the economic variables we are investigating. If we then find that economic variables under investigation respond to the changes in carbon prices that we have identified, we can be reasonably confident that the changes in carbon prices have caused the subsequent changes in the economic variables.

To address this challenge, we rely on the approach developed by Känzig (2023), which isolates variation in futures prices in the EU ETS market over short time windows around selected regulatory announcements or events that affected the supply of emission allowances. Specifically, we calculate these ‘surprises’, or shocks, as the change in carbon prices relative to the prevailing wholesale electricity price on the day before the announcement or event. They are ‘surprises’ because they are unexpected. Moreover, because these changes are related to regulatory events, we can be confident that they are not connected to business cycle phenomena, such as changes in consumer confidence, unexpected changes in monetary policy, and so on.

Macro-evidence on the effects of carbon pricing shocks

With our carbon price surprise series in hand, we can investigate the impact of changes in the carbon price on a set of macroeconomic variables. The variables we focus on are real GDP, the nominal interest rate on two-year government bonds, headline consumer prices, the energy component of consumer prices, equity prices, and credit spreads on corporate bonds. We do so for 15 European countries that are in the EU ETS. We also include the UK, which was part of the system until 2020, and has since operated a similar system independently.

We adopt an econometric approach that allows us to trace through the effects of an unexpected change in carbon prices today on the economic variables that we are interested in over the next three years. Furthermore, this approach also allows us to consider how the impact of carbon pricing shocks on macroeconomic variables depends on countries’ emissions intensity of output (ie CO2 emissions per unit of GDP). In particular, we consider the macroeconomic response of a high-emissions economy relative to an average-emissions economy, where high-emissions is defined as a country whose carbon intensity is one standard deviation above the average carbon intensity in our sample.

Our econometric analysis finds that an unexpected one standard deviation increase (0.4%) in carbon prices leads, on average three years after the shock, to a decline in GDP (-0.3%) and equity prices (-2.5%), and to an increase in consumer prices and their energy component (0.4% and 3% respectively), interest rates (5 basis points), and credit spreads (15 basis points).

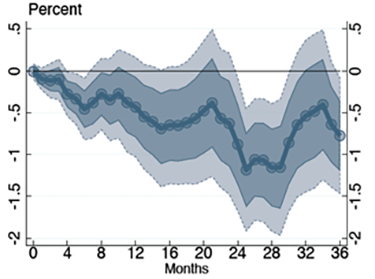

Moreover, countries with higher CO2 intensity tend to experience larger effects from the carbon pricing shock, with a larger drop in output and equity prices, a larger increase in consumer prices, and a larger increase in interest rates and credit spreads. This is shown in Chart 1, which plots the responses of macroeconomic variables in higher-emissions intensity economies relative to those with average emissions intensity.

Chart 1: Baseline effect of carbon pricing shocks – high-emissions countries

Notes. Effect of a one standard deviation (0.4%) increase in the carbon policy surprise series for a country whose levels of CO2 are one standard deviation above the average level of CO2 relative to the average country. Shaded areas display 68% and 90% confidence intervals computed with heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation robust standard errors (two-way clustered, at the country-month level).

A drawback of this country-level analysis, however, is that the CO2 intensity variable may be correlated with other country-specific characteristics that affect the strength of the transmission of carbon pricing shocks. It is therefore difficult to be particularly sure that the larger responses in higher emissions intensity countries are because they are more emissions intensive.

Firm-level evidence on the effect of carbon pricing shocks

A way around the identification problem in the aggregate data – that the results there may be influenced by other factors that correlate with emissions intensity – is to conduct our analysis using firm-level data. In particular, our research considers the impact of carbon pricing shocks on firms’ equity prices, a variable we choose because it provides an effective summary of firms’ performance and is readily available at high frequency for many firms across many countries. In doing so, we can also include many firm-specific controls in our econometric model, which provides reassurance that we are indeed capturing the impact of different emissions intensity on economic responses.

Chart 2: Effect of carbon pricing shocks – high-emission firm equity prices

Notes. Effect of a one standard deviation increase (0.4%) in the carbon policy surprise series on equity prices in the firm-level data. The chart reports the equity price response of a high-emission firm (ie whose CO2 emissions are one standard deviation above the average CO2 emissions) relative to the average firm. Shaded areas display 68% and 90% confidence intervals computed with heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation robust standard errors (two-way clustered, at the firm-month level).

Our firm-level econometric analysis finds that an unexpected one standard deviation increase (0.4%) in carbon prices leads to declines in firms’ equity prices of -1%, on average three years after the shock. It also finds that firms with higher CO2 emissions experience larger drops in their equity prices following a carbon pricing shock, with a peak impact of more than 1%. This is shown in Chart 2, which plots the response of equity prices for higher CO2 emission intensity firms relative to the response of firms with average emission intensity.

To rationalise these empirical findings, in our research we build a theoretical model with green and brown firms, where brown firms are subject to climate policy analogous to the carbon pricing shocks. This shows that the bigger impact on brown firms’ equity prices reflects the direct increase in their costs associated with the higher carbon prices. Green firms are also affected, which reflects spillovers through product markets and those for capital and labour. Moreover, we show that, while the shocks will hit green and brown firms differently, the effects are not offsetting across firms. As a result, the carbon pricing shocks can lead to significant effects on macroeconomic aggregates, such as GDP and inflation.

Conclusion

In our research, we have shown that carbon pricing shocks have effects on economic variables and that these effects are greater for more emissions-intensive countries and firms. Analysis like this is important for helping the Bank’s policy committees understand the effects of such shocks on the wider economy, allowing them to calibrate an appropriate response in order deliver their objectives for monetary and financial stability.

Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi and Alex Haberis work in the Bank’s Global Analysis Division. This post was written while Federico Di Pace was working in the Bank’s Global Analysis Division, and Brendan Berthold is a Macro and Climate Economist at Zurich Insurance Group.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “The heterogenous effects of carbon pricing: macro and micro evidence”

Publisher: Source link